Galatea is a short story by Madeline Miller, written after The Song of Achilles and in the middle of her working on Circe. As an expert in classics and a teacher in Latin and Greek at high schools, Miller is surely expected to draw her inspiration from their host of works. This time it’s Metamorphoses by Ovid―a classic hailed by many as a romantic, happy-ever-after love story but, to Miller herself, has a disturbingly misogynistic undercurrent in it. Hence the need not only to retell but to twist it.

Unlike Circe, which is a retelling but still in the mythical world, Galatea seems to be a blend of everything. It’s a classic with mythological elements set in our modern narrative―which, as we can see it widely in almost every aspect and any sense, is not that much different from that of the ancient times.

The story starts with, and this might raise a question in any reader’s mind, Galatea being and waking up in a closed room with only a nurse attending her and a doctor who regularly checks up on her. She is confined in bed, she must lie down, and every time she suggests an idea of her taking a walk outside to warm herself in response to the nurse and the doctor finding her body too cold, they banish it immediately. The reason is―it seems likely so―none other than their being afraid of her husband, besides being paid by him.

As for the motive behind this confinement, though, it is not clear until Miller takes us through the already known narrative by Ovid, which serves as the backstory. Galatea was a statue, “born” out of an ivory, and the man sculpted her eventually married her when she came to life. They have a daughter, Paphos, who is smart and rebellious and has no qualms about saying no to her tyrant of a father. And Paphos’ smartness is not enough for a governess, so Galatea asks her husband for another tutor (the previous one was sacked for looking at her, which her husband detested). And, of course, her husband refuses the idea.

Unfortunately, if you want to say so, Paphos is not a daddy’s girl and, unlike her obedient mother, cannot be confined in anything by anybody. When she is not allowed to go outside and learn more she is restless, up to the point of not caring if she disturbs her father working at home with her behavior. So Galatea, who loves her daughter so much that even her husband is jealous of her, takes her to the countryside to play just as they usually did. Galatea tells Paphos not to tell her father, for he will surely be very angry should he know; and then, together, they walk out on the street as secretly as they can. But they are too conspicuous―with their looking “as pale as milk” and Galatea herself is an obvious, outstanding beauty that makes her husband wary and anxious and keen on keeping her from anybody else. Long story short, they are caught, and this is why Galatea is consequently punished.

Galatea, as a story, is not being subtle. It tells the reader loud and clear that there are always disturbing ideas about women in society―either it’s ancient or modern. Ideas that the most perfect woman (wife?) is the one with a perfect, outstanding beauty, moral purity and total obedience; that if a man kiss you and you’re not blushing then you are shameless; that any (other) man cannot look at you when you are strikingly pretty; that your sole and only function as a woman is to bear and rear children for your husband and to satisfy his sexual needs. A pretty woman in a cage, full stop. Nothing else.

These ideas have taken root for generations and no amount of protests, negation, or feminist movements could pull them out or even, at the very least, prevent them from spreading wider. They do not apply to everybody, yes, but still, they exist in almost every culture we know, in almost every society there is. If this is a strong enough reason for some (many?) women to feel angry, then it is justifiable. If this is a strong enough reason for Miller to sound angry in her writing, then it is justifiable. Galatea’s voice is as calm as she seems obedient, but her rage is there and profound. She looks like a “yes, Sir” wife but she is not stupid, and the dissatisfaction with her caged life is secretly seething until finally she chooses her own way.

Madeline Miller’s Galatea is merely a short retelling, but its twist is impactful. And what makes it even more relevant (today) is not only our constant need to rebel against something which is badly against our will, but also our need to state firmly that these ideas cannot go on any longer.

Rating: 4.5/5

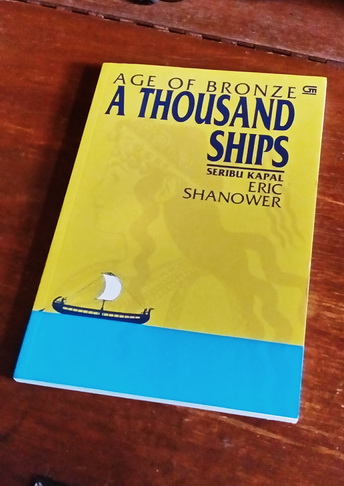

The war between Troy and Achaea is perhaps the most famous one in classic literature, the most memorable, the most talked-about, the most retold in modern era. It doesn’t only revolve around revenge, dignity and heroism, but also passion and reckless love. It has been so often reproduced in many forms of popular culture, and now it appears in the form of graphic novel, entitled A Thousand Ships. It doesn’t exactly retell the story of the Trojan War, but the beginning, how it comes to the horrific end. Eric Shanower, the illustrator responsible, has made a tremendous effort to represent the old legend in pictures, and tried his best to formulate a narrative adaptation to accompany his drawings which would be easily fathomable.

The war between Troy and Achaea is perhaps the most famous one in classic literature, the most memorable, the most talked-about, the most retold in modern era. It doesn’t only revolve around revenge, dignity and heroism, but also passion and reckless love. It has been so often reproduced in many forms of popular culture, and now it appears in the form of graphic novel, entitled A Thousand Ships. It doesn’t exactly retell the story of the Trojan War, but the beginning, how it comes to the horrific end. Eric Shanower, the illustrator responsible, has made a tremendous effort to represent the old legend in pictures, and tried his best to formulate a narrative adaptation to accompany his drawings which would be easily fathomable. Wanita sering kali tidak punya pilihan, dan tidak bisa berkata tidak. Sebelum banyak dari kaum perempuan di zaman modern menangisi kenyataan ini, kisah-kisah wayang Jawa kuna sudah sejak lama menyiratkannya, dan kisah Drupadi dalam epos Mahabharata adalah salah satunya. Seno Gumira Ajidarma menuliskan kembali kisah sang dewi nan cantik cemerlang ini dalam sejumlah cerita pendeknya, yang kemudian dijadikan satu sehingga terbaca sebagai sebuah novel yang utuh. Ditemani ilustrasi-ilustrasi apik karya Danarto serta bait-bait puisi yang memantik akal dan rasa, buku yang diberi judul Drupadi ini tidak hanya berbicara tentang penderitaan yang harus dialami wanita, tetapi juga peran dan apa yang sanggup mereka lakukan dengan kekuatan tersembunyi yang mereka miliki.

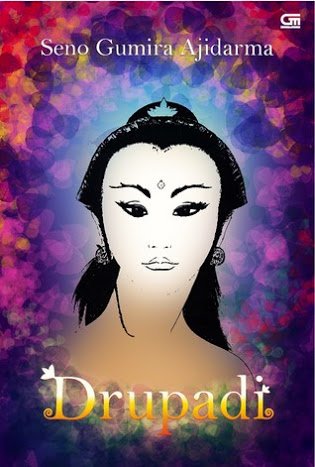

Wanita sering kali tidak punya pilihan, dan tidak bisa berkata tidak. Sebelum banyak dari kaum perempuan di zaman modern menangisi kenyataan ini, kisah-kisah wayang Jawa kuna sudah sejak lama menyiratkannya, dan kisah Drupadi dalam epos Mahabharata adalah salah satunya. Seno Gumira Ajidarma menuliskan kembali kisah sang dewi nan cantik cemerlang ini dalam sejumlah cerita pendeknya, yang kemudian dijadikan satu sehingga terbaca sebagai sebuah novel yang utuh. Ditemani ilustrasi-ilustrasi apik karya Danarto serta bait-bait puisi yang memantik akal dan rasa, buku yang diberi judul Drupadi ini tidak hanya berbicara tentang penderitaan yang harus dialami wanita, tetapi juga peran dan apa yang sanggup mereka lakukan dengan kekuatan tersembunyi yang mereka miliki. Namun Seno Gumira Ajidarma tidak hanya menceritakan derita yang mesti dialami Drupadi sebagai seorang wanita. Dalam bab berjudul Wacana Drupadi, SGA menggambarkan betapa sang dewi sudah tak sanggup lagi memendam dendam di dalam hati dan menuntut kelima suaminya agar menuntut balas kepada para Kurawa. Dari tuntutan Drupadi inilah berkobar Perang Bharatayudha, di mana Kurawa dikalahkan oleh Pandawa dan Drupadi dapat memenuhi sumpahnya: mengeramasi rambutnya dengan darah Dursasana. Dari sini dapat dilihat betapa perang bisa terjadi “hanya” karena dendam dan tuntutan dari seorang wanita. Tetapi dari sisi lain juga dapat dilihat betapa balasan dari menghinakan seorang wanita mampu menyeret seratus orang kesatria beserta seluruh pasukannya pada kematian. Ini adalah kekuatan wanita, kekuatan tersembunyi yang tidak diperoleh dari penempaan fisik maupun penggunaan senjata.

Namun Seno Gumira Ajidarma tidak hanya menceritakan derita yang mesti dialami Drupadi sebagai seorang wanita. Dalam bab berjudul Wacana Drupadi, SGA menggambarkan betapa sang dewi sudah tak sanggup lagi memendam dendam di dalam hati dan menuntut kelima suaminya agar menuntut balas kepada para Kurawa. Dari tuntutan Drupadi inilah berkobar Perang Bharatayudha, di mana Kurawa dikalahkan oleh Pandawa dan Drupadi dapat memenuhi sumpahnya: mengeramasi rambutnya dengan darah Dursasana. Dari sini dapat dilihat betapa perang bisa terjadi “hanya” karena dendam dan tuntutan dari seorang wanita. Tetapi dari sisi lain juga dapat dilihat betapa balasan dari menghinakan seorang wanita mampu menyeret seratus orang kesatria beserta seluruh pasukannya pada kematian. Ini adalah kekuatan wanita, kekuatan tersembunyi yang tidak diperoleh dari penempaan fisik maupun penggunaan senjata.

Sitti Nurbaya (1920) is an Indonesian classic known to and hailed as a masterpiece by everyone in the country, even by those who never actually read the book. Every time there’s a young girl being married off to a man she never desires, we, Indonesians, will immediately, and stupidly, say that the girl suffers the same fate as Sitti Nurbaya. But most people get the story wrong, for it’s not about a girl being married off to some old, notoriously rich man her father picks for her. Set in Padang, West Sumatra (the land of Minangkabau people) the novel unfurls the story of a very young girl named Sitti Nurbaya who suffers a tragic fate in which she has to lose not only her love (by her own choice), but also everything she has. She is the daughter of a very rich merchant, befriending, and later falling in love with, Samsulbahri, a young man of noble birth. They could have been married, if not for her father’s sudden bankruptcy after the conflagration that destroys his shops and the evil scheme his competitor plays against him. The situation forces Nurbaya to forget about her dream and give up her happiness for her father instead. In order to help him pay his debts, she ends her relationship with Samsulbahri (without his knowing it) and marries Datuk Meringgih, who is also a bloody rich merchant in their city. She’s not happy, of course, and before she can see it coming, a fate worse than death befalls her and takes her life.

Sitti Nurbaya (1920) is an Indonesian classic known to and hailed as a masterpiece by everyone in the country, even by those who never actually read the book. Every time there’s a young girl being married off to a man she never desires, we, Indonesians, will immediately, and stupidly, say that the girl suffers the same fate as Sitti Nurbaya. But most people get the story wrong, for it’s not about a girl being married off to some old, notoriously rich man her father picks for her. Set in Padang, West Sumatra (the land of Minangkabau people) the novel unfurls the story of a very young girl named Sitti Nurbaya who suffers a tragic fate in which she has to lose not only her love (by her own choice), but also everything she has. She is the daughter of a very rich merchant, befriending, and later falling in love with, Samsulbahri, a young man of noble birth. They could have been married, if not for her father’s sudden bankruptcy after the conflagration that destroys his shops and the evil scheme his competitor plays against him. The situation forces Nurbaya to forget about her dream and give up her happiness for her father instead. In order to help him pay his debts, she ends her relationship with Samsulbahri (without his knowing it) and marries Datuk Meringgih, who is also a bloody rich merchant in their city. She’s not happy, of course, and before she can see it coming, a fate worse than death befalls her and takes her life. Unlike the classic, which is a tragic story by nature, the contemporary Puya ke Puya is lighter in its tone, though the story itself is all about the pursuit of heaven in the afterlife. The Tempo’s Best Book 2015 relates generally about what the people of Toraja (it derives from the words to riaja, which means “the people from above”) in South Sulawesi have to do for a family member who has just passed away to be able to find their way to heaven. Rante Ralla, a known noble man of his ethnic group, dies a sudden death while drinking ballo, some kind of alchoholic drink from Toraja. Rante’s son, Allu Ralla, refuses to hold rambu solo, a huge and costly funeral for the deceased, for he has no money and his father hardly leaves him a penny. His uncle urges him to sell their family’s land to the mining company that has been sucking their village dry for years so he can have the money to hold a proper ceremony instead of just burying his father in a low-cost, Christian way. It’s not only about money, though, for Allu doesn’t see any point in performing an “old custom” which is not relevant anymore. Thus, he insists on going on “the modern way”.

Unlike the classic, which is a tragic story by nature, the contemporary Puya ke Puya is lighter in its tone, though the story itself is all about the pursuit of heaven in the afterlife. The Tempo’s Best Book 2015 relates generally about what the people of Toraja (it derives from the words to riaja, which means “the people from above”) in South Sulawesi have to do for a family member who has just passed away to be able to find their way to heaven. Rante Ralla, a known noble man of his ethnic group, dies a sudden death while drinking ballo, some kind of alchoholic drink from Toraja. Rante’s son, Allu Ralla, refuses to hold rambu solo, a huge and costly funeral for the deceased, for he has no money and his father hardly leaves him a penny. His uncle urges him to sell their family’s land to the mining company that has been sucking their village dry for years so he can have the money to hold a proper ceremony instead of just burying his father in a low-cost, Christian way. It’s not only about money, though, for Allu doesn’t see any point in performing an “old custom” which is not relevant anymore. Thus, he insists on going on “the modern way”.

In 1936’s Indonesia was barely on the verge of its independence, but the pressure for gender equality seemed greater and greater. Through Layar Terkembang, Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana appears to imply that the urge to embrace modernity, in every aspect possible, couldn’t be held back anymore. Told in a form of short novel, the thought-provoking story of this classic Indonesian work unfolds what it was like in the past when an independent woman fighting for a place in society had to war with her own desire for love that demanded her letting go of her stand and cause.

In 1936’s Indonesia was barely on the verge of its independence, but the pressure for gender equality seemed greater and greater. Through Layar Terkembang, Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana appears to imply that the urge to embrace modernity, in every aspect possible, couldn’t be held back anymore. Told in a form of short novel, the thought-provoking story of this classic Indonesian work unfolds what it was like in the past when an independent woman fighting for a place in society had to war with her own desire for love that demanded her letting go of her stand and cause.